The Lower Mekong region is home to a remarkably diverse range of plants, animals, and minerals and other natural resources. Due to competing social, economic, cultural, and other interests, the richness and diversity of the region is considered to be one of those at highest risk. Thus, the region has a long history of environmental and natural resource protection, conservation, and advocacy.

What is the environment?

The international community typically understands “environment” as separate from humans, placing human activity at odds with animals, plants, and natural resources. For example, this is the approach taken in the UN’s 2017 Draft Global Pact for the Environment, the IUCN’s 2021 Marseille Manifesto, and 2022’s 30×30, a cornerstone of a new framework agreed by the parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. While it is uncontestable that some human activity has placed animals, plants, minerals and water at risk, and is also responsible for climate change, this understanding of “environment” has impacted how environmental conservation is practiced in the region. In particular, it has been noted that the dominant frameworks of conservation – and the 30×30 commitment specifically – have not safeguarded people, especially the Indigenous Peoples and other local communities who are typically displaced as a product of this type of work.1 Some international conservation organisations, such as the IUCN, are moving in the direction of actively recognising IP as stewards of the environment and include humans in their definition of “nature”. However, IP around the region are clear that extra effort needs to be made to ensure that IP are included as equal partners in this work.2

Biodiversity hotspot

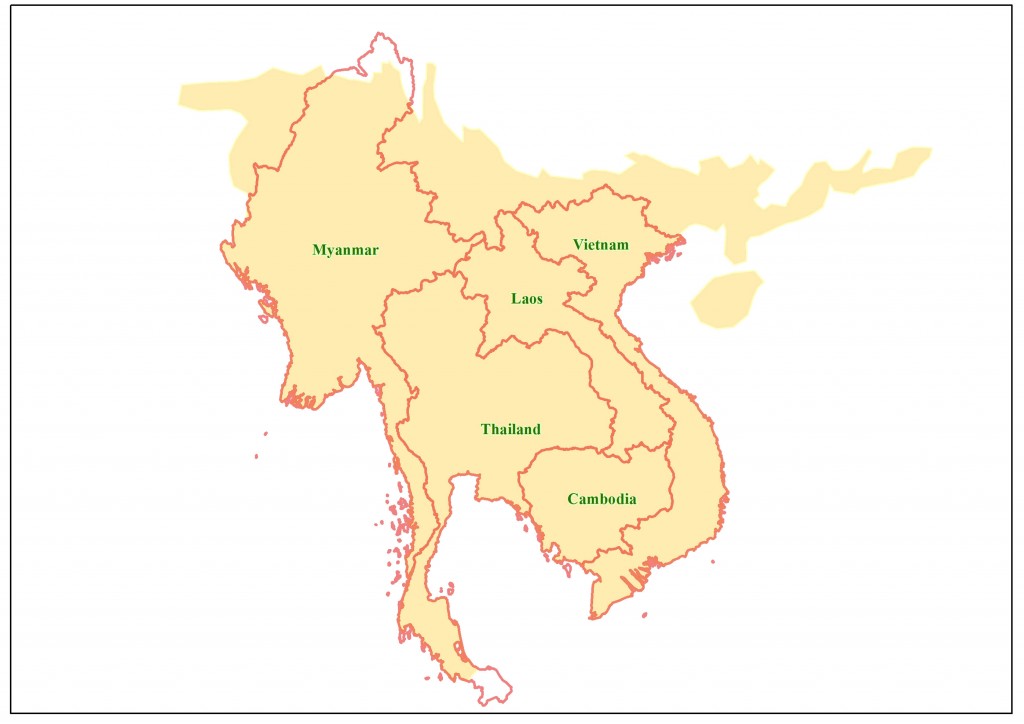

Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Vietnam and Thailand are almost completely encompassed within what Conservation International has designated the Indo-Burma hotspot, one of the world’s top ten critical areas for biodiversity. This hotspot also has the most people living in it. Biodiversity hotspots are defined by the number of native species it contains.3 In particular it includes a great number of endemic birds, and plants, with over 1300 birds and 470 mammal species identified in 2020.4 The 2,373,000 km2 area includes all of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos and most of Myanmar and Thailand, as well as parts of Bangladesh, Malaysia and southern China. This hotspot continues to be a priority investment area for the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Wildlife Conservation Society also works in the Mekong region of the Indo-Burma hotspot, focusing on slowing the decline of forest cover and biodiversity.

Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot

At the heart of the Indo-Burma hotspot is the Mekong River, which WWF has included as a key site for its wildlife conservation efforts. WWF indicates that 224 new animal species were reported in the region in 2020. Other international conservation organisations, including Fauna and Flora International, also have a significant presence in the region. Together, these organisations are the main institutional drivers of environmental protection in the region. Each of these organisations have named threats that drive their conservation priorities, but agro-industrial investment, hydropower dams cross over each of CEPF, WWF, and WCS.5

In addition to the riverine ecosystem around the Lower Mekong Basin, the region includes a wide variety of other ecosystems, including mixed wet evergreen, dry evergreen, deciduous, and montane forests, as well lowland floodplain swamps, and seasonally inundated grasslands. Limestone karsts, with their own unique ecosystems, characterize the landscape in many areas—most famous among them is Vietnam’s Ha Long Bay. The region’s coastlines and marine areas are also rich in biodiversity.

The picturesque and biodiverse limestone karsts and caves of Vietnam’s Ha Long Bay have made it a World Heritage site. Photo by Bob DeGraff, taken on 21 February 2015. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Generic.

What are natural resources?

Natural resources have typically been defined with an economic focus, with the OECD stating that they are “natural assets (raw materials) occurring in nature that can be used for economic production or consumption”.6 From this perspective, Western scientists have worked to account for “ecosystem services” (or the economic, cultural, social and physical benefits that are provided by healthy ecosystems), which has impacted environmental research and policy development.7 For instance, this has driven the work of REDD+, which is a key process in the region.

In the Mekong region, water, minerals, forests and forest products, fish and fisheries, and agricultural products are key natural resource drivers of the economy. The complex hydrology of the Mekong supported the production of 109 million tons of paddy rice in 2017. It also supports the world’s largest freshwater fishery, producing 25% of the world’s freshwater catch.

Timber and non-timber forest products—including resins, bamboo, and rattan—produced by the region’s forests are traded both locally and internationally. Many local communities, including of Indigenous Peoples, have traditional and livelihood practices that centre around these materials. Various fishing and farming practices are also central to local communities. However, in the last 3-4 decades, the rush to modernize and industrialize has significantly altered landscapes. Before the 1970s, most of the region was highly forested, but now just 13 percent of primary forest remains.8 There has been an increase in forest loss in all countries in the region, except Cambodia, since 2001. At least 310 species of fish are listed as threatened in the five Lower Mekong countries.9

Mountains around Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photograph by zoutedrop, Flickr (cropped), taken 25 June 2008. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC), which includes the Mekong countries, adopted the ASCC Blueprint 2025 in 2015. This is intended to guide cooperation to “include the conservation and sustainable management of biodiversity and natural resources, promotion of environmentally sustainable cities, climate change adaptation and mitigation, as well as promotion of sustainable consumption and production towards circular economy”.10 The four priority areas of cooperation are: (i) conservation of sustainable management of biodiversity and natural resources, (ii) promotion of environmentally sustainable cities, (iii) response to climate change, and (iv) sustainable consumption and production.11

Related to environment and natural resources

References

- 1. Joe Eisen and Blaise Mudodosi. 2021. 30×30 – a brave new dawn or a failure to protect people and nature? Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 2. Somini Sengupta, Catrin Einhorn and Manuela Andreoni. 2021. There’s a Global Plan to Conserve Nature. Indigenous People Could Lead the Way. Accessed July 19, 2022. Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact. 2022. Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, and their critical role in protected and conserved areas. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 3. Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Biodiversity Hotspots Defined. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 4. Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. 2020. Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot: 2020 Update. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 5. Threats named by these organisations include hunting and trade of wildlife, agro-industrial plantations, hydropower dams, agricultural encroachment, infrastructure and logging (CEPF); hydropower development, climate change, illegal wildlife trade and habitat loss (WWF); investments in agro-industry, hydropower, mining, and other industries (WCS).

- 6. OECD. 2001. Natural Resources. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 7. Klaus Birkhofer et al. 2015. Ecosystem services – current challenges and opportunities for ecological research. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 8. WWF 2015. WWF Living Forests Report. http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/living_forests_report_chapter_5___saving_forests_at_risk.pdf accessed 19 May 2017.

-

9. International Union for the Conservation of Nature. “Red List, Table 5: Threatened Species in Each Country (Totals by Taxonomic Group).” Accessed 3 April 2015. http://cmsdocs.s3.amazonaws.com/summarystats/2014_3_Summary_Stats_Page_Documents/2014_3_RL_Stats_Table_5.pdf.[/ref] The development of hydropower, the anticipated expansion of mineral extraction, and the transition of agrarian systems to agro-industrial production are set to alter landscapes still further.

The Lower Mekong region is considered to be at high risk for climate change. By 2030 the Mekong basin’s mean temperature is likely to increase by 0.79°C, with greater increases for the colder catchments in the north.12 Lebel, L., C.T. Hoanh, C. Krittasudthacheewa and R. Daniel, eds. 2014. Climate Risks, Regional Integration and Sustainability in the Mekong Region. Kuala Lumpur: SIRD. Accessed 4 April 2015. http://www.sumernet.org/content/e-version-sumernet-book-now-available. View on Open Development Datahub

- 10. ASEAN. Environment. Accessed July 19, 2022.

- 11. ASEAN. Environment. Accessed July 19, 2022.